|

3/11/2022 Lenna vs. ExcavatorThis is a picture from a hot day in August 2021, just another day in a livestock guardian dog's life.

Lenna has developed into a bit of a leader. A great one, at that. We know when someone arrives at our farm because she is always the first to alert. And being located 700 feet from the road, with a heavily wooded driveway, the humans are not the first to hear someone coming. Lenna heard the excavator before we did. Generally leery toward a new visitor, she quickly alerted, and we reassured her that everything was fine, that this was someone who was here to do a job, and that this person would not be taking her chickens. She became calm, yet still cautious at the sight of the machine that, little did she know, was many thousands of pounds heavier and many feet taller than her (and much noisier). What's interesting, though, is that I truly believe that she felt she could take on this, this . . . . thing that she had never seen before, whatever her mind considered it to be. The heart of an LGD has no defined area or volume. It is not confined to a perimeter like Lenna's fence, and it doesn't evaporate in the hot August sun after a rain. It overflows, but on a plane that is never ending. Quite possibly the most important part of a farm "ecosystem", livestock guardian dogs are the heart of a farm. This blog post contains our farm family's "top 5" reasons why LGDs are amazing. Realize, it's not easy to pick just 5 reasons, so this is not an exhaustive list, but it is one that showcases what we value most from our working dogs. They are, in fact, so amazing, we would never have a different type of dog. Reason 1: Livestock guardian dogs are intelligent There are varying degrees of differences in body sizes, personalities, and strengths from one breed of LGD to another, but there is one consistent trait to all well-bred LGDs: they are smart. They have the ability to think through tough situations when confronted by a predator, and are able to intimidate, deter, or outsmart a threat to their flock with amazing critical thinking. Because of this, they often do not need to be physically confrontational. LGDs also understand key words and phrases and differing voice inflections. Most can be trained to commands, such as sit, stay, down, and drop it. When something may be amiss on the farm, they use their intelligence to figure out what it may be. Reason 2: Livestock guardian dogs are gentle Whether it's a newborn kid or lamb, a small chicken, a piglet, or a toddler, LGDs, although large in size, are gentle-giants around other animals and humans. Though these dogs could easily trample smaller animals, they have an awareness of their surroundings, and it is not an unusual sight to see a chicken practically standing on a lounging LGD or a LGD bonding with a newborn mammal. They are even known to assist in the clean-up process after birth, licking the newborn kid or lamb. This gentleness also corresponds with young toddlers who are a part of the shepherd's family. Livestock guardian dogs are calm with their movements around a young child, careful to tolerate excitement and spontaneity. Reason 3: Livestock guardian dogs are strong willed

Though the trait of being strong willed could cause strife between shepherd and dog if an LGD has not been trained or bonded, it is one that is needed out in the field when guarding the flock. This is why it is necessary to set boundaries and train and spend time with the pup while it learns the routines, interactions, sights, and sounds of the farm. It is especially important during the first 6 months of the dog's life. Later, when the guardian-in-training shows its shepherd that it is ready, it will be tasked with the important job of keeping a flock safe from predators without human assistance. Due to the nature of their work, LGDs need to be able to demonstrate how strong willed they are by being allowed to independently make decisions and confront threats. Livestock guardian dogs are determined and do not shy away from something that is out to get their flock. And they have a work ethic that never falters. Reason 4: Livestock guardian dogs are genetically distinct Dogs have evolved side-by-side with their human counterpart for many years, creating breed specific standards to suit a wide variety of different human needs. Livestock guardian dogs are no different. LGDs can adapt well to different living situations, including being a family companion; however, they thrive when working to protect other animals from predators. In basic terms, their distinct large build, double coat, protective instincts, intelligence, and personality traits make them suitable for jobs on the farm or in the field. The human-canine connection part of this evolution should not be undervalued. What's important to the shepherd will be important to the dog. Reason 5: Livestock guardian dogs are like family Livestock guardian dogs are also an extension of family. When bonded with their shepherd, they will do their job dutifully, every day. Rarely, if at all, are they slack. Being extremely loyal, they never forget what was taught. It is well worth the shepherd's time to bond with the pup, and, once that bond is established, the dog will not want to disappoint the shepherd when it is ready to protect the other animals. LGDs will show unwavering love toward their family and shepherd. 12/10/2021 ZoukOur handsome Nigerian Dwarf herd sire is MeadowMist SW Zouk.

This series of photos was taken when Zouk was a little over a year old. It shows his gentle, inquisitive nature. He is a buck who loves his ladies but also loves his humans. Here, he is enjoying a good brushing from our toddler, interrupted by a sweet kiss from her. He is always happy to meet a farm visitor, especially if they pet him and give him the attention he so enjoys. When he is not getting taken care of by a toddler or chewing his cud, Zouk enjoys climbing on the fallen trees and stumps that can be found in our "15 acre wood". 11/25/2021 LennaGuardian. Smart. Alert. Confident. Strong. Fast. Agile. A watcher, both on the perimeter and in the middle of her flock. Devoted. Has a job. Does it day and night . . . relentlessly. I mean RELENTLESSLY. Farm greeter. Will frisk you upon entrance. Family. Companion. Man's best friend. The overused cliché holds water here. For this: we love her. Meet Lenna. Lenna came to us from Florida. She was whelped of a Maremma x Anatolian Shepherd cross. She is a product of her genetics, large enough to fend off predators, yet quick and agile enough to also catch them if needed. She is just as much a part of our family as our one and half year old daughter. Working when we are sleeping or away, she is the boss of our farm and keeps everything in check. Without her, it is inconceivable how many livestock, chickens in particular, we would have lost. She does everything we ask. She is near 100% on recall, and she can hold a "Stay" for 5-10+ minutes when we are in a bind. Other commands that are second nature are sit, down, drop it, and not yours. She can walk with us on a leash like she is a 10 pound dog. When we talk, she listens. She is smart. She knows what we are saying. We didn't know we needed a livestock guardian dog. We didn't even know that there were different livestock guardian dog breeds. Here in Michigan, it is common to see and hear of farms that have Great Pyrenees. There was a lot to learn at first. It was a new part of farming that we had not considered before. After losing chickens to aerial predators one summer, and knowing that there are fox, bobcat, coyote, and bear that live nearby, we needed answers. What is our defense against predators at our farm? When goats are kidded, or when baby piglets are born what truly protects them? There was no answer to that question other than this: a fence, of course. That was a legitimate answer for the goats and pigs, though not totally predator proof, and not an acceptable alternative for our poultry. We have Icelandic chickens, brahma chickens, and guinea fowl. Free ranging them without fences was a non-negotiable cornerstone of our farming philosophy. That's when we decided we needed a livestock guardian dog. So far, in Lenna's young life as a guardian, there has been a dead opossum, over 25 porcupine quills (a better story to tell in person), the time a stray dog was fast approaching (we witnessed this one), the chasing off of a coyote, a skunking, and a whole lot of unknown. I say unknown because we know we have predators, aerial and on the ground, yet we will never truly know, other than the cold hard proof stated above, how many times Lenna has guarded her flock. How many predators has she barked off? How many chickens has she saved? To what else do we owe her for her unconditional guardianship?

Until a person has a livestock guardian dog, one truly doesn't know what they are missing in life. These dogs are exceptional in every way. They are, to put it succinctly, the rudimentary version of what man's best friend aspired to, with a wolf's heart. When we have to leave our farm, we do it with confidence knowing that our animals are taken care of. For all this, we owe Lenna our unconditional love as companions at Terroir Farm. Lenna means "lion's strength". She certainly lives up to her name. 11/11/2021 Are There Piglets In There?One warm July evening, shortly after Clover's arrival at Terroir Farm, Todd told me to look inside Clover's hog barn. He had watched her build a nest earlier that day, which meant she would likely be delivering within 24 hours. How exciting! I hurried over to take a look. "Guinea hogs are especially gentle with the young pigs ... Right before farrowing, they may behave differently, as in they carry small items or hay or grasses into the hut or to their chosen birth place to build a nest." Excerpt taken from Curly Tales, the American Guinea Hog Association Newsletter I hopped the short hog panel fence right away and gave Clover, who was taking a drink, a "Hi there" and quick pat. When I made my way back to her shelter for a peek at the nest she was building I was surprised by a movement in the hay. I yelled back to Todd, "either there's a mouse in here, or she has already had the piglets!" That's when I realized I was in a vulnerable position. I was down on my hands and knees, peeking in on the newborn babies, and Clover was somewhere in the pen behind me. Yikes! I scrambled up to see what she would do. . . nothing. She was not concerned about my presence at all. Phew. As they nursed, slept, and explored in their first weeks of life, Clover showed excellent mothering skills to her first litter of 7 piglets. She was attentive and gentle, and even displayed her protective instincts when we picked up the piglets to assess their gender and body condition. A squealing piglet is sure to get mom's attention fast! She grunted her displeasure as we handled her babies but never acted overly aggressive or tried to bite us. Our first farrowing experience was surely memorable. We are thankful to Becky Mahoney for picking out such a gentle hog to be our first "mama pig" here at Terroir Farm. Check out our expected guinea hog litter page if you are interested in adding these gentle hogs to your homestead. Click HERE to learn more about American Guinea Hogs.

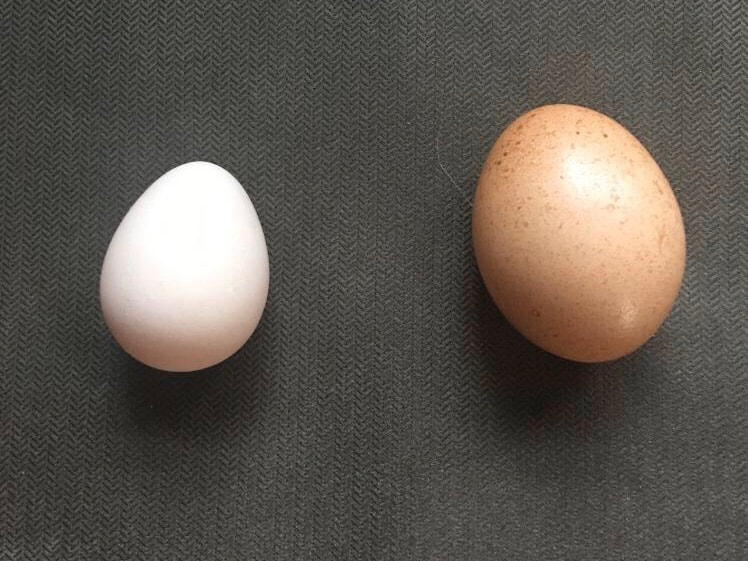

Amanda 7/14/2021 One of these Eggs is not like the OtherHow do you know the difference in the quality of food? Take an egg, for example. An egg is an egg is an egg is an egg, right? After having guineas on our farm for over two years now, we have learned that the answer to that questions is a big, steadfast NO! You can get a chicken to lay an egg if they are fed organic, non-organic, soy, or soy-free. You can get a chicken to lay an egg if they are factory farmed and confined to small, tight spaces, or if they live on a holistic farm and are allowed to free range on grassy and/or woodland pastures. The beauty of an egg, however, is that you can literally SEE and TASTE the difference. There are even subtle nuances between two eggs that come from two different farms that value similar farming practices. Now multiply this "difference" in sight and taste by 10. Divide it by 3. Take out the remainder of 5. Add two and multiply it by 25. WOW. Just kidding. No need to do math. Just look at the pictures on this blog post, and, folks, meet the GUINEA EGG! On our farm we refer to guinea eggs simply as, . . . drum roll, please . . . The Golden Egg. We believe this wholeheartedly. No family member or friend gets to try guinea eggs unless there is a special reason to give them some. Right now, they are the caviar of our woods, a seasonal delicacy to be savored, and, well, sautéed in a pan, preferably with a nice amount of butter or lard. Guinea egg yolk was the first thing our daughter ate as she began to try food at 6 months old. You can think of many reasons why a guinea egg could be compared to gold. These reasons have many positive connotations associated with them. All of them apply. *** Let's take a brief intermission and get one thing straight before I continue to travel with you down this blog post. Guineas are loud and difficult to train. They have a couple negative stigmas attached to them and there is a lot of truth to them. But if someone looks beyond, and can get past the occasional loud "BUCK WHEAT, BUCK WHEAT, BUCK WHEAT" and "CHI-CHI-CHI-CHI-CHI" noises, it's well worth it. *** Guineas are the feathered version of a livestock guardian dog. They are ever watchful, curious little creatures that will sound the alarm if there is a predator, especially aerial. They can run so fast they look like they are flying on a broomstick. If anything is different on our farm, they are there to check it out. Was the wheelbarrow left in a different place? Was there a shovel left on the ground? The guineas know, trust me. They have a way about them of sticking their necks out really far and bobbing their heads up and down if they are cautious of something new. We jokingly mimic this all the time. Our guineas have access to the same fermented organic, soy and corn free, non-gmo grain that our chickens do. They are happy to eat it, but in the spring, summer, and fall, that is just a small supplement to their diet of bugs, grasses, strawberries (they love them), field mice, toads, salamanders, etc. They fend for themselves a lot of the time, certainly a very good trait to have for a farmer's pocketbook. Our guineas hide their nests in the thicket of the woods, never more than a couple hundred feet from their coop. The guinea cock builds the nest. He picks the perfect spot and rubs his body against the ground to create a nest indentation. The hens then use this nest every day. He stands guard while they lay. The ultimate companion. We love our guineas at our farm. With their unique appearance, speed, vigor, nimbleness, and curiosity they are one of the animals that are an absolute pleasure to have around. Best of all, they have retained a lot of the wild traits that have been bred out of chickens. A guinea cock will not run the hens ragged and is an absolute protector, willing to sacrifice his life in order for the hen (or hens) to be safe.

Most of all, guineas are a true testament to what food looks like if animals are raised how they should be: lots of space and freedom to roam freely, foraging for high quality, natural food. It is our farm family's opinion that no egg will ever compare to the little oval shells filled with "caviar" that we get from our woods. The Golden Egg. CHI-CHI! 7/12/2021 Around the Farm . . .Things are a little busy right now at Terroir Farm. New animals and new infrastructure have taken ahold as the defining "ripe fruit of the summer". With so much "new" (new LGD, goats, chickens, and hogs) It's easy to feel like one is on a never-ending time crunch to get things done. Summer only lasts a short few months in northern Michigan. All the time, the animals don't stop eating, growing, and doing a little bit of providing. With all of this work, it will be exciting when they start to do a LOT of providing. They will be the future of our farm. But all the while things take time. It's not easy to build a farm from the ground up. Literally. When we moved here, nestled into the woods more than 700 feet from the road, surrounded by red oak, silver and red maple, white pine, beech, hemlock, birch, hop-hornbeam, and aspen, we thought it would be a perfect place to live and raise a family. As we got into the "back-to-the-land movement" things evolved. Being so heavily wooded, trees have their place. They are certainly necessary because of everything that they provide: a wide variety of foliage for foliage-eating goats, shade, fruit (acorns, hop-hornbeam nuts, beech nuts), beauty, and all of of the spiritual qualities that are harder to put into words. They, however, need to be tended and cared for in order to thrive. Untouched forests have their place, but a land that is in balance and harmony with livestock needs a little tender loving care. Every time we add more pieces to our farm, the forest must be manicured first, with an ideal space that allows the specific type of animal to thrive. Trees need to be chosen as "keepers" for the future. Trees need to be chosen as firewood for winter warmth. A lot of thought must go into each tree that is kept or cut down. Many of these decision will be made trying to look decades into the future. So things take a while when adding new. This all being said, as the title of the post depicts, there is indeed a metaphorical circle "around" all of this work. If things are done right, the land AND the animals needs are taken into consideration. Everything relies on all of the interconnected parts. Those parts are vast and branch further than I can even comprehend. We are just at the cusp. The farm that we envision will be highly sustaining, possibly even having parts that are self-sustaining. As we add, in order to thrive, we must subtract. We must go through times of heavy work. It is through the completion of this work that a lucky farmer starts to see the potential of this circle. Healthy, vigorous trees and soil builds life-sustaining forage for animals that, in turn, provide sustenance, and allows a small farm family a glimpse at what things could be like if we take the time to carefully implement what we have planned. "Around the farm" isn't just conversational. It's transcendental. 5/25/2021 When I First Milked a GoatSicily, the white goat in the picture above, is the first goat I ever milked. Before I could milk a goat, I needed a goat in milk - a doe who has kidded and is still producing milk. My mom and her husband came up to visit last week. They, having NO farm animal experience whatsoever, graciously agreed to pick up these two goats on the way and put them in the back of their car. One of these goats, Sicily, was in milk. I had it all planned out: My parents would pick up the goats at 4:00 in the afternoon and deliver them by sundown. Well, you know what they say about the best laid plans. . . after a series of unfortunate events, they arrived at 2:00 in the morning. Those poor goats were calm in the car the entire time, but I’m sure they were ready to stretch their legs! The next morning, because Sicily was in milk she needed, well, milked! My mother was astounded. "How do you know how to milk a goat!?" She, who raised me in a rather typical suburban neighborhood, could not believe it. I gave her the obvious response, "I watched a video online." First I led Sicily up onto the milk stand and put her head through the headpiece. She promptly took it out. The stand was built by our friends at Serendipity Farms for their Nubian goats and it was too wide for this little Nigerian Dwarf goat’s head. What to do? I walked to the garage and grabbed an extra dog collar and looped that through her collar and then around the milk stand. Now that she was more or less secure, I put some goat food in her bowl so she could eat breakfast while I milked. I sat on an upturned 5 gallon bucket and cleaned her udder. Then, I put a bowl under her and did my best imitation of the technique I had viewed online. And... nothing. No milk. So I tried again, pinching tighter with my thumb and forefinger. After a minute of trying I got a bit out, but it dribbled down my hand. Who knew it was so dang hard to milk a goat!? Throughout all of this I am wearing my toddler in a backpack-style carrier. To keep her, myself, and the goat calm, I began to sing. And soon, thin steady streams of milk were going into the bowl. I’m doing it! I’m milking a goat! My goat! I couldn’t get the coordination down to use both hands at once, though I did try. I kept switching sides and I found it far easier to use my dominant hand. Go figure, right? I didn’t really think about that kind of thing beforehand, but it makes sense. . . In the end, I got about one cup of milk. This is the beginning of a very fulfilling part of my day. To milk a goat, I would say, is experiencing joy in liquid form. When I am milking, I feel a connection to all the goatherders and milkmaids that have come before me. Providing this basic, nourishing liquid for my family in such a tangible way, there's nothing else like it. Milking a goat is one of those things that seems rather inconsequential until you try it. ~Amanda 4/21/2021 Fish GutsLenna, our Livestock Guardian Dog, is 100% on recall, until recently. I have heard of the "teenage stage" in LGD's, during which they regress in their training and even misbehave around the animals they protect, suddenly chasing a chicken out of the blue. Lenna is about that age, at 8 months old, so I began to believe she had begun rebelling, so to speak. When she is off tether she will roam around the perimeter of the yard and then find a nice stick to chew on and settle in nearby, where she can keep an eye on us and the animals. Usually. Recently she has been going to the same twin pines off into the woods where I can just barely see her. She will stay there sniffing and sniffing. Figuring it to be a deer bed or some nice racoon poop, I call her off. "Lenna, here!" She doesn't even look up. I put on my angry face and attempt to march a direct line toward her through the thick, tangled underbrush, alternating between post-holing in the soft snow and tripping over branches where the snow has meted. When I am about 30 yards away she finally acknowledges my existence and trots over with her head down. I grab the leash she's dragging and march her back through the soft snow and tangled branches to where I had called her. "Lenna, I said here! ... good girl!" *Play this scene on repeat. For two weeks.* Last night, the family is going for a walk in the woods to roughly mark out where to lay the underground fence for Lenna. As we walk, we get to those twin pines. There, on the ground before us, is a colorful, scaly pile of half-frozen perch carcasses. We have not been fishing recently. It is still winter in Northern Michigan and we don't ice fish. A little detective work has us following a set of footprints in the snow that lead to a neighbor's back door. Turns out our neighbor's son has been filleting his daily catch and dumping the remains "back in the woods for the racoons to take care of." We politely explain that racoon is our 80 lb. dog who has not been hungry for her breakfast as of late. All of a sudden Lenna's reluctant wait-til-she's-close recall becomes understandable. I wouldn't pass up a perch dinner, and apparently, neither would she. ~ Amanda 4/5/2021 Christmas Morning SurpriseLenna was 6 months old and used to being out with the chickens by the time her first Christmas came around. She has never injured a chicken. She enjoyed her growing freedom around the farm and during chores could choose to do her own thing nearby or come with me. Usually, she chose to come with.

On Christmas morning I was doing chores and Lenna followed. I started with the buck pen - the furthest out in the woods. Lenna opted to stay outside the fence and sniff around rather than go in to greet her favorite buck, Zouk. As I was in the barn refreshing the hay and water I hear a rustling in the woods. I poke my head out of the barn and see a deer. Lenna is about 50 feet away from me, on the opposite side of the fence. I watch her intently, unsure of what she will do. This is her first encounter with a deer. She stands and stares. The deer stares back. At the exact moment the deer begins to move our youngest layer announces to the world she's laid an egg. Her exuberant clucks sound like a siren. Lenna, without hesitation, sprints to the coop. Sits by it. And barks her big girl bark towards the deer, who takes off as fast as a bolt of lightning, leaving with a quick flash of her white tail. Although a small act, it displayed a big step in her maturing process. Our Christmas gift from this young girl was showing us she will defend the birds that we have been teaching her to value. Merry Christmas Lenna. |

AuthorWhen she's not baking bread Amanda enjoys going for walks with her girls and making goats milk ice cream. Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed